©Fredrik Naumann/Felix Features

Interview with Norwegian NCP member Synne Homble from the NCPs annual report 2016.

The OECD gives individuals, local communities and organisations a place to go when they are concerned about how multinational enterprises are affecting people and the environment. This makes the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises unique.

‘No other international instruments for promoting responsible business have a corresponding grievance mechanism,’ explains Synne Homble of the Norwegian NCP.

To ensure impartiality and trust in the process, the NCP can only consider instances reported by organisations or private individuals.

Easy to get defensive

‘It’s easy to get defensive if you are the subject of a complaint. At the same time, many Norwegian companies have done thorough, systematic work on corporate social responsibility, and recognise that dialogue is important and that the process can be a source of learning,’ Homble points out.

She knows what it is like to be scrutinised by the NCP.

In 2009, when Homble was Chief Officer at Cermaq – one of the world’s leading aquaculture companies – a complaint was filed against the company by Friends of the Earth Norway (Naturvernforbundet) and the Forum for Development and Environment (ForUM) concerning its activities in Chile and Canada. The complaint concerned fish health, working conditions and indigenous rights.

‘We first thought the complaint was unfair, before we arrived at a joint solution through mediation. The process helped us to establish dialogue with the organisations that filed the complaint, where we had to listen to each other and understand both sides of the matter. The NCP did an important job in sorting out poorly substantiated claims and ensuring an unbiased dialogue,’ explains Homble.

Creates trust

The grievance mechanism is non-judicial, but the NCP relies on key legal concepts like the adversarial principle and documentation requirements.

‘This is important to ensure that the case is well elucidated and to gain the trust of all the affected parties,’ Homble believes.

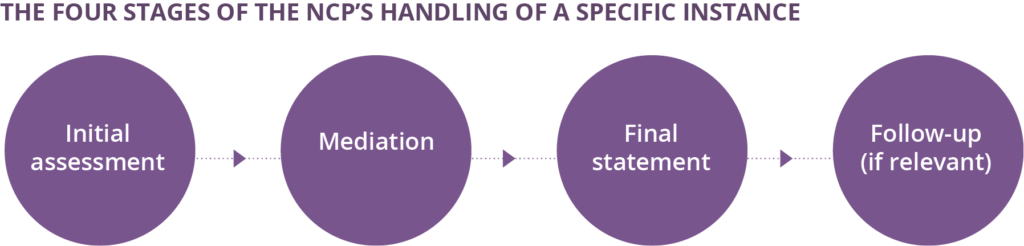

When a complaint is reported, the NCP first carries out a procedural assessment. Are the matters reported covered by the grievance mechanism? Does the complainant have a right to represent the violated parties? The secretariat also provides guidance in how to set up and formulate the complaint.

‘Claims must be substantiated and related to the Guidelines,’ Homble points out.

The company that is the subject of the complaint is then given an opportunity to make a statement. When this is received, the NCP makes a decision on whether to accept the complaint for consideration. The complaint is not made public until it is taken under consideration.

Dialogue is the key

‘The aim is not to hold anyone up to ridicule, but to achieve improvements and find solutions,’ says Homble.

The best solution is when the parties, through dialogue and support from the NCP, are given the tools they need to resolve the conflict themselves. The agreement is laid down in a joint statement. The NCP also offers free mediation.

‘Dialogue is a goal in itself. The process creates a platform for mutual understanding, not only with a view to solving a specific instance but also to resolve future problems before they arise,’ says Homble, and adds:

‘We have also seen examples of parties who have not reached agreement during the complaints process continuing their dialogue and reaching a solution later on,’ explains Homble.

Deterrent effect

If the parties fail to reach agreement, the NCP issues its own final statement, giving its opinion on whether the Guidelines have been violated and providing recommendations on the road ahead.

‘This is a strong deterrent factor,’ says Homble, and points out that public criticism from the NCP can be a burden, especially for companies that are normally perceived as responsible. They must answer to the public, organisations, shareholders and investors.

‘The risk of a negative statement can be enough to make the parties look for a voluntary solution,’ Homble believes.

Great variation

The Guidelines cover all key aspects of corporate social responsibility. This means that the complaints vary greatly.

‘The NCP has considered cases concerning requirements for financial investors, indigenous people, stakeholder engagement and local communities, working conditions and the environment. The 2011 revision of the Guidelines added a new chapter on human rights, which has since been an important topic. In general, Norwegian companies have difficulties ensuring that their suppliers meet the expected standard,’ says Homble.

Only companies from the countries that have endorsed the Guidelines can be the subject of a complaint, but the complaint can concern any country in which the companies operate.

‘It is a challenge that civil society in the countries with the weakest legislation and inadequate court systems is not familiar with the OECD’s grievance mechanism,’ says Homble, and concludes:

‘The goal is not to receive as many complaints as possible, but to ensure that the companies know how to prevent and avoid violations of the Guidelines.’

Text: Marianne Alfsen